Building FinOps Teams: Roles, Structures, Career Paths

Summary: Choosing and building the right FinOps team structure is key to success, ranging from Centralized (for strong governance and early adoption) to Distributed (for fast local decision-making in large organizations) or a balanced Hub-and-Spoke Model. An example core team can include a FinOps Lead, Analysts, and Engineers, whose responsibilities are often defined and dependent upon the infrastructure and reporting lines of the organization. Success requires strong executive sponsorship and positioning the team to influence technical and financial decisions. See real world organizational examples in the Paper’s supplementary slide deck.

At the heart of a FinOps discipline is the dedicated FinOps team — a group charged with enabling cost transparency, aligning stakeholders, and driving data-informed decisions about technology investments. The way the team is designed and structured serves as a cornerstone for building a strong FinOps practice and culture across the organization.

Learn the common roles and structures within FinOps teams, the division of responsibilities, potential career paths, and how these teams are positioned within the broader organizational landscape. Remember: FinOps is a shared responsibility across many organizational roles, the FinOps Team we refer to in this paper describes the individuals whose primary job function is a FinOps practitioner and (in most cases) have direct reporting line up to the FinOps Lead.

FinOps Team Roles

FinOps teams come in various shapes and sizes, and no two teams are exactly alike. It is important to note that not every organization requires a dedicated FinOps team from the start. For those just beginning their FinOps journey, a single part-time or full-time resource may be all that’s needed.

As organizations mature their FinOps practice, the need for a structured team becomes more apparent, whether that’s a small group of specialists or a larger, more comprehensive function. In many organizations, a single person may wear multiple hats, blending responsibilities of both a FinOps Analyst and a FinOps Engineer.

As organizations mature and grow, other roles begin to emerge, such as dedicated FinOps Engineers and FinOps Data Analysts. See below for information on the most common roles within the FinOps function.

| Role | Description | Reports to | Recommended FinOps Foundation Certifications |

| FinOps Lead | Head of the FinOps Practice, overseeing all FinOps functions, responsible for shaping and driving the FinOps practice, culture, and collaboration across the organization. | Varies widely, but often into some senior engineering or cloud Director or VP function. |

|

| FinOps Analyst | Business-aligned practitioner executing day-to-day FinOps capabilities. Partners with teams to execute various actions such as forecasting, anomaly management, rate and usage optimization, etc. to drive accountability and maximize value of technology investments. | FinOps Lead or high-level FinOps Analyst |

|

| FinOps Engineer/Architect | Builds, implements, and maintains the technical infrastructure in support of the FinOps function. Developing processes and automations for budgeting, anomaly alerts, forecasting, optimization, invoicing and chargeback, etc. ensuring accurate, scalable, reliable solutions. | FinOps Lead or high-level FinOps Analyst |

|

| FinOps Data Analyst | Collects, processes and delivers usage and cost data via reports, dashboards, and visualizations that empower FinOps team members and other key stakeholder personas to make informed, data-driven decisions. Often drives commitment discount purchases. | FinOps Lead |

|

| FinOps Financial Analyst | Tracks, analyzes and reports technology spending with a focus on budgeting, forecasting, and accurate reporting of actual spend while driving accountability and aligning investments with business priorities | FinOps Lead |

|

| FinOps Educator | Responsible for FinOps training & enablement initiatives that build FinOps knowledge and skills across the organization. Promotes cultural adoption and FinOps awareness, fosters accountability, and equips teams with the practices and mindset needed to embed FinOps into daily operations. | FinOps Lead or high-level FinOps Analyst |

|

Other notable roles that may appear in FinOps teams but are less likely are:

- FinOps Technical Writer: creates clear, concise, and actionable documentation for FinOps processes, tools and best practices. Produces user guides, training materials, and other documents that help stakeholders across the organization understand and effectively incorporate FinOps actions in their role.

- FinOps Program Manager: drives the planning, execution, and governance of FinOps initiatives across the organizations coordinate with cross function teams, managing timelines, tracking outcomes and ensuring on-time, on-scope, on-target delivery of projects aligned to organizational goals.

The right mix of FinOps roles depends heavily on your organization’s size, cloud maturity, and the complexity of your cloud environment.

- Smaller or early-stage FinOps practices may only need a single FinOps Analyst or Financial Analyst to provide visibility into spend and ensure accountability. However this person is also likely to be taking on responsibilities across data analyst, engineering, education, and lead roles.

- Mid-size or maturing practices often expand into multiple and more specialized roles, such as a FinOps Lead, FinOps Analyst, FinOps Engineer/Architect to implement automation and a FinOps Data Analyst to enable accurate, actionable reporting.

- Large or highly complex environments typically require a dedicated FinOps Lead to coordinate across business units, plus a mix of all other roles.

Building a FinOps team is an incremental process. The roles and skills required to foster a FinOps culture will evolve over time, but typically require a mix of leadership, communication, analytical, and technical skills to support the work described in the FinOps Framework, especially its Personas Section.

Team Structure

The structure of a FinOps team matters because it directly influences how organizations manage technology spend, align stakeholders, and scale accountability. A clear and intentional team design ensures responsibilities are well defined, avoids duplication of effort, and provides the right balance of strategic leadership and hands-on execution. As organizations mature in their FinOps journey, the team’s structure becomes a critical enabler of collaboration and execution of FinOps. There are three common structures of FinOps teams.

Centralized

Centralized FinOps: when the entire FinOps team sits in one functional area.

This structure is best for organizations early in FinOps adoption or when governance, control, and alignment are needed. Centralized FinOps teams are well positioned for driving accountability and ownership as well as standardizing processes and reporting. Some centralized FinOps teams may find it takes longer to develop relationships with and to influence other key stakeholders when trying to partner on FinOps capability activities.

Distributed

Distributed FinOps: when members of the FinOps team are distributed across multiple different business units, directly embedded and reporting into other teams such as finance, product, and engineering.

This structure is best suited for organizations that do not require standardization of FinOps processes and reporting and where the individual teams (product, engineering) are adept at holding themselves accountable to maximizing the value of their technology investments and driving data-informed decision making. The decentralized FinOps team structure enables fast decision making and variety in FinOps implementation to meet the needs of the individual teams.

Additionally, the distributed model is well suited for having the FinOps practitioner also be an expert for the area they are supporting, versus having a FinOps practitioner from a central team needing to become familiar with all of the functional areas they are assigned to support. However, this structure also makes it harder to maintain central and consolidated visibility. Training, education, and communication are essential for distributed teams to share and implement best practices and to avoid duplication in effort, tooling. etc. and to coordinate efforts.

Hub and Spoke

Hub and Spoke Model: when there is both a core, central FinOps team in one functional area and FinOps members directly embedded into other teams. This model is a blending of the centralized and decentralized team structures where the members embedded into distributed teams will often have a dotted line reporting back to the central FinOps team.

This structure is best for organizations which are scaling their FinOps practice and needing to balance standard processes, and consolidated visibility with versatility and quick decision making encouraging both organizational governance and operational agility.

The Hub and Spoke Model requires clear lines of responsibility and coordination between the hub and spokes as organizations risk confusion and duplication if boundaries are not well defined and understood. Some organizations have a centralized FinOps function but still get the feel & benefits of a hub and spoke model by using champions or other similar mechanisms as pseudo spokes.

The following table outlines how FinOps team structures often align with organizational size, maturity, and the complexity of cloud usage and FinOps scopes. It is intended as guidance rather than a prescriptive model, highlighting common patterns seen in practice while recognizing that real-world structures may vary.

| Team Structure | Org Size | FinOps Maturity | Cloud / Scopes Complexity | Best for |

| Centralized | Any | Any | Any | Organizations developing their FinOps practice or needing strong governance |

| Decentralized | Large | Any | Complex | Teams needed fast decision making and variety in FinOps processes |

| Hub & Spoke | Med-Large | Med-High | Complex/Growing | Organizations looking to balance central controls with speed and versatility. |

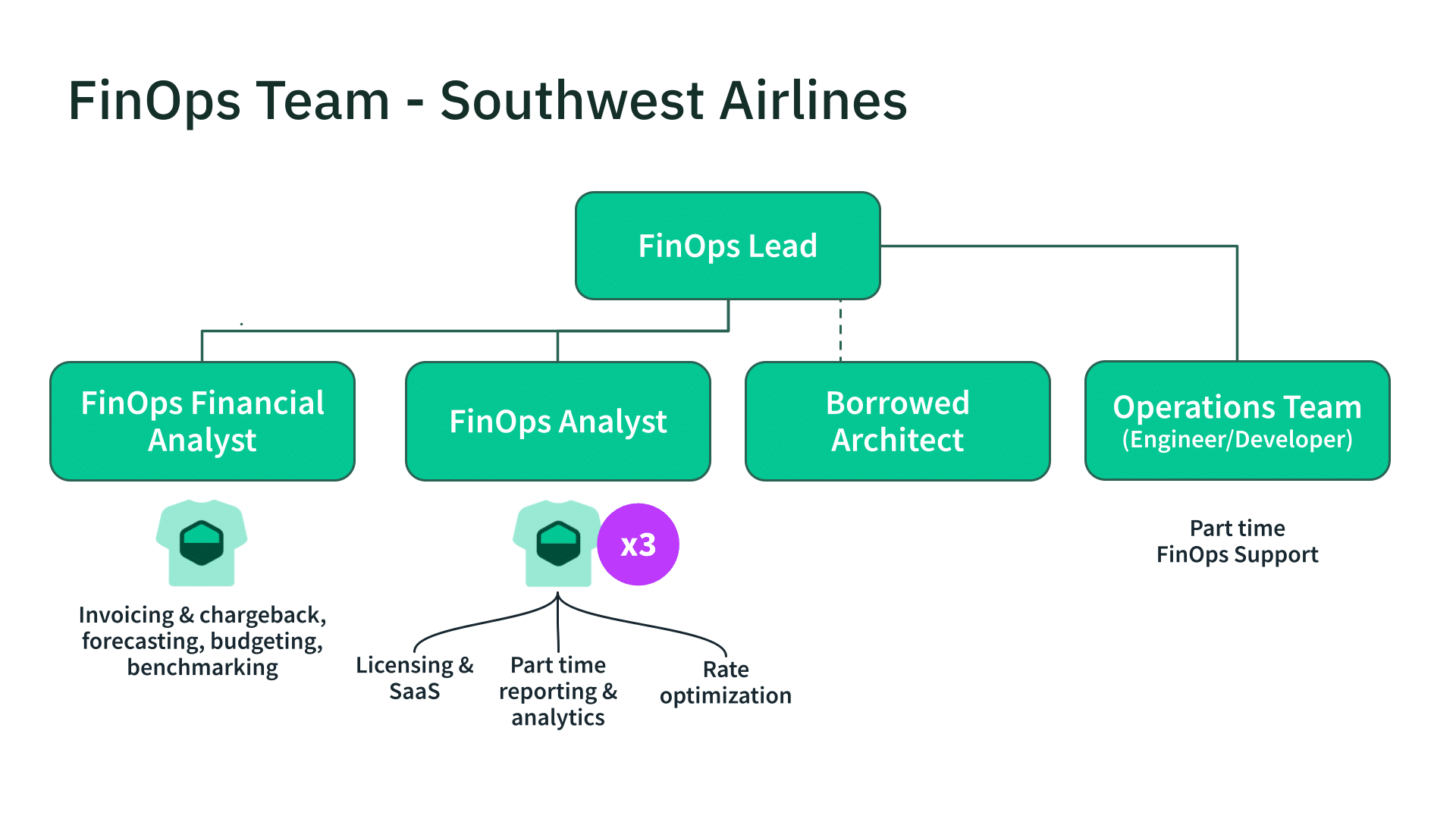

See the following examples of FinOps Teams in place at various organizations.

Source: FinOps Teams – Real World Examples – Google Slides

As an additional example, Natalie Daly shared at X Day Tokyo 2025 how the FinOps team at HSBC evolved from a small group of three full-time practitioners in 2019 to a robust organization of 44 by 2025. Their growth mirrored the expansion of FinOps scope and responsibilities within the company, as well as increasing capability maturity.

Having explored the common roles and structures of FinOps teams, the next step is to look at how responsibilities are divided, how alignment is maintained, and how teams scale appropriately for their organization.

Division of Responsibilities, Alignment & Sizing

Before deciding how many FinOps practitioners you need or what each of them should focus on it’s critical to understand both the current state of FinOps in your organization and the short to medium-term goals of your practice. The right structure depends on your maturity, scope, and business priorities.

Conducting a FinOps Assessment can help you to understand your current and target states and inform decisions about role responsibilities and team size. This section offers general guidance drawn from community experience to help you shape those decisions effectively.

Within the FinOps team there is a balance between roles of strategic and operational responsibilities. The FinOps Team Lead is primarily accountable for strategic alignment, stakeholder engagement, and capability maturity. While they maintain visibility into operational activities, their day-to-day involvement in tasks such as forecasting or optimization tends to be lighter.

By contrast, FinOps Analysts are deeply engaged in operational execution—building forecasts, detecting anomalies, and running optimization cycles. Their focus is tactical, though they may have a smaller role in shaping strategy.

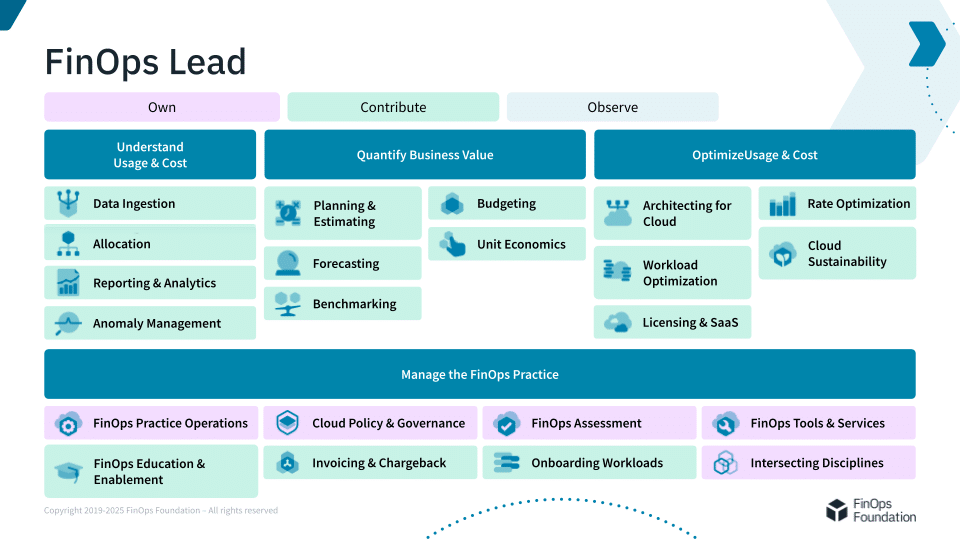

Own, Contribute, Observe

See below for general guidance about the responsibilities of each role as it pertains to the various FinOps Capabilities. These images depict typical areas of responsibility for each FinOps role assuming all/most roles are present in the organization.

- Own: The primary driver and executor of the activity. This role performs the hands-on work and is responsible for ensuring the task is completed. In some cases, there may be owners elsewhere in the organization but from within the FinOps function this is the owner. For example, Finance may own budgeting overall but from within the FinOps team the responsibility primarily lies with the FinOp Financial Analyst.

- Contribute: Actively participates in the activity but is not the primary driver. Contributors may provide tools, guidance, or perform supporting tasks that influence outcomes, but they do not own execution.

- Observe: This role has minimal or indirect involvement in the activity, perhaps no involvement at all. They may stay informed of progress or outcomes.

Here is an example of “Own, Contribute, Observe” for the FinOps Lead. Source: FinOps Teams – Real World Examples Slides

Once core responsibilities of each role are identified, the next step is determining how to align the team to different areas. This is particularly important when a FinOps team has multiple of a given role – this is most often seen with FinOps Analysts. In these cases, organizations typically divide responsibilities along natural lines of:

- Business Alignment: Assign members to specific business units, products, or portfolios to ensure cost accountability at the source.

- Geography/Region: For global orgs, align to time zones and localized requirements.

- Cloud Provider/Domain: Assign members to AWS, Azure, GCP, or other domains in multi-cloud environments

- Scope: Divide responsibility across infrastructure types (public cloud, private cloud, on-prem, data center, AI/ML workloads).

Team size is shaped by multiple factors. The total amount of spend under management is an obvious one, with some organizations choosing to establish a guideline about the number of team members required to support a given spend threshold.

For example, for every “x” million in spend one FinOps Analyst is needed, but it is equally important to consider the number of business units, products, and team supported, the complexity of the technology environment, and the level of maturity of the FinOps practice. For organizations where the bulk of FinOps responsibilities are pushed to the edge (as could be with hub and spoke), the responsibilities of the core FinOps team could be less heavy and a small number of practitioners could cover broad ground.

This may also apply to organizations which are leveraging supplementary resources such as contractions, consultants, and champions. Organizations deepening their FinOps maturity and with growing complexity of scope however may discover a need for more specialized and dedicated capacity amongst team roles.

The right team size is less about hitting a particular ratio and more about ensuring that the FinOps function is resourced appropriately to meet the organization’s financial and operational goals. Beyond questions of size, though, lies another important consideration: how to extend or enhance the team’s capabilities through supplemental support.

Supplementing FinOps Teams

Not every team can or should be built entirely from full-time staff. Contract resources, consultants, or even specialized tools and services, including automation or AI, can help fill the gaps. Applying AI to FinOps capabilities allows for augmenting a team’s effectiveness without increasing headcount. Capabilities such as Forecasting and Anomaly Management are well suited for AI solutions given their reliance on historical data analysis, pattern recognition, and continuous monitoring.

As FinOps maturity and AI adoption increase, more advanced teams may deploy AI agents to support Rate Optimization, Workload Optimization, and Planning & Estimation capabilities. It is important to note that AI augmentation does not eliminate the need for specific FinOps roles. Instead, practitioners can manage a broader portfolio of responsibility and focus on driving collaboration and outcomes.

FinOps Champions are individuals in FinOps-adjacent roles across the organization who are selected to participate in a formal Champion program. Champions can be leveraged to extend FinOps awareness and process within their own team without adding direct hires to the FinOps team and yet, this type of champion approach can also be leveraged in organizations with informal champions programs too. Alternatively, FinOps teams may borrow resources or leverage part time use of individuals in other areas of the organization for additional support.

Factors that may influence a decision to bring in outside expertise include:

- Stage of FinOps Maturity: Early in the journey, consultants or similar resources can accelerate adoption and help design a scalable operating model or to help establish training, culture, and best practices across multiple teams and address change management.

- Specialized skills: Roles like FinOps Engineer/Architect or FinOps Educator may require technical expertise that’s hard to hire or only needed for certain phases or projects.

- Capacity constraints: When budgets, headcount, or timelines make it unrealistic to build a large in-house team.

Ultimately, the best approach is to scale your FinOps team in step with your technology usage and organizational priorities, blending full-time hires, supplemental human resources, and tooling to fit your needs.

Positioning Within the Larger Organization

Now that we’ve discussed team structure, let’s talk about effective team positioning – FinOps teams tend to report to the executive who is responsible for making technology investments successful. As a result, most organizations tend to leave the CTO or CIO as responsible for FinOps. In organizations more focused on financial controls, FinOps may sit under the CFO.

The State of FinOps Report consistently shows the CTO as being the most likely role to own the FinOps function. Data from the State of FinOps Report indicates that 40% of respondents indicated the CTO owned the FinOps function versus 20 percent of respondents who indicated ownership belonging to the CIO as being the next most likely scenario.

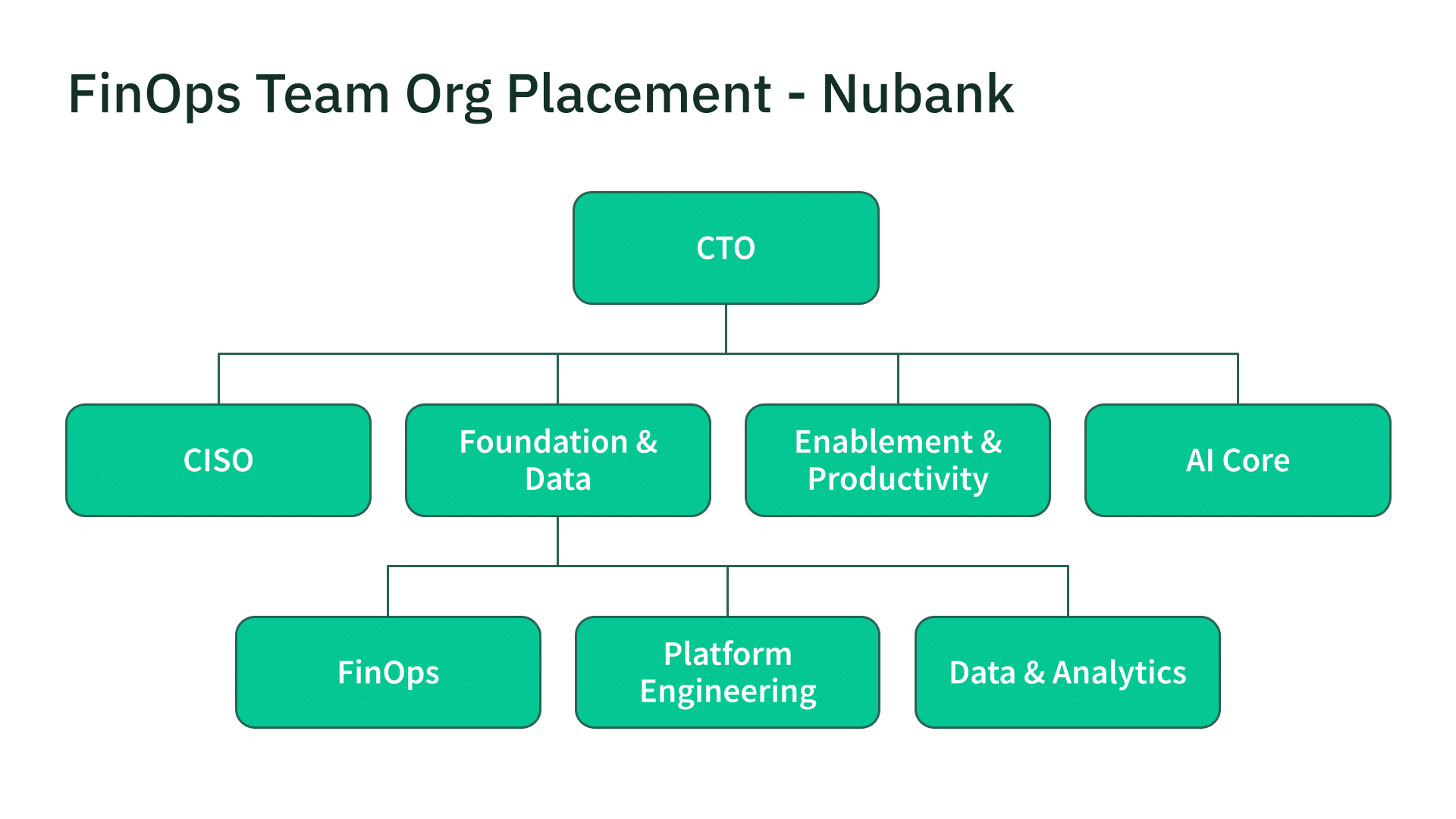

Here is a FinOps Team placement example from Nubank. Source: FinOps Teams Real World Examples Slides

Considerations for FinOps organizational positioning, and the ease with which the function can execute, include access, influence, visibility, and executive alignment. FinOps is inherently a cross functional practice and its success depends on the ability to influence behavior across key stakeholder groups such as finance, engineering, and product.

It is critical to position the FinOps function in a way that provides both visibility and accessibility. This access must flow both ways: FinOps practitioners need consistent engagement with their key partners, and those partners need to be able to easily reach FinOps as they collaborate to execute FinOps capabilities.

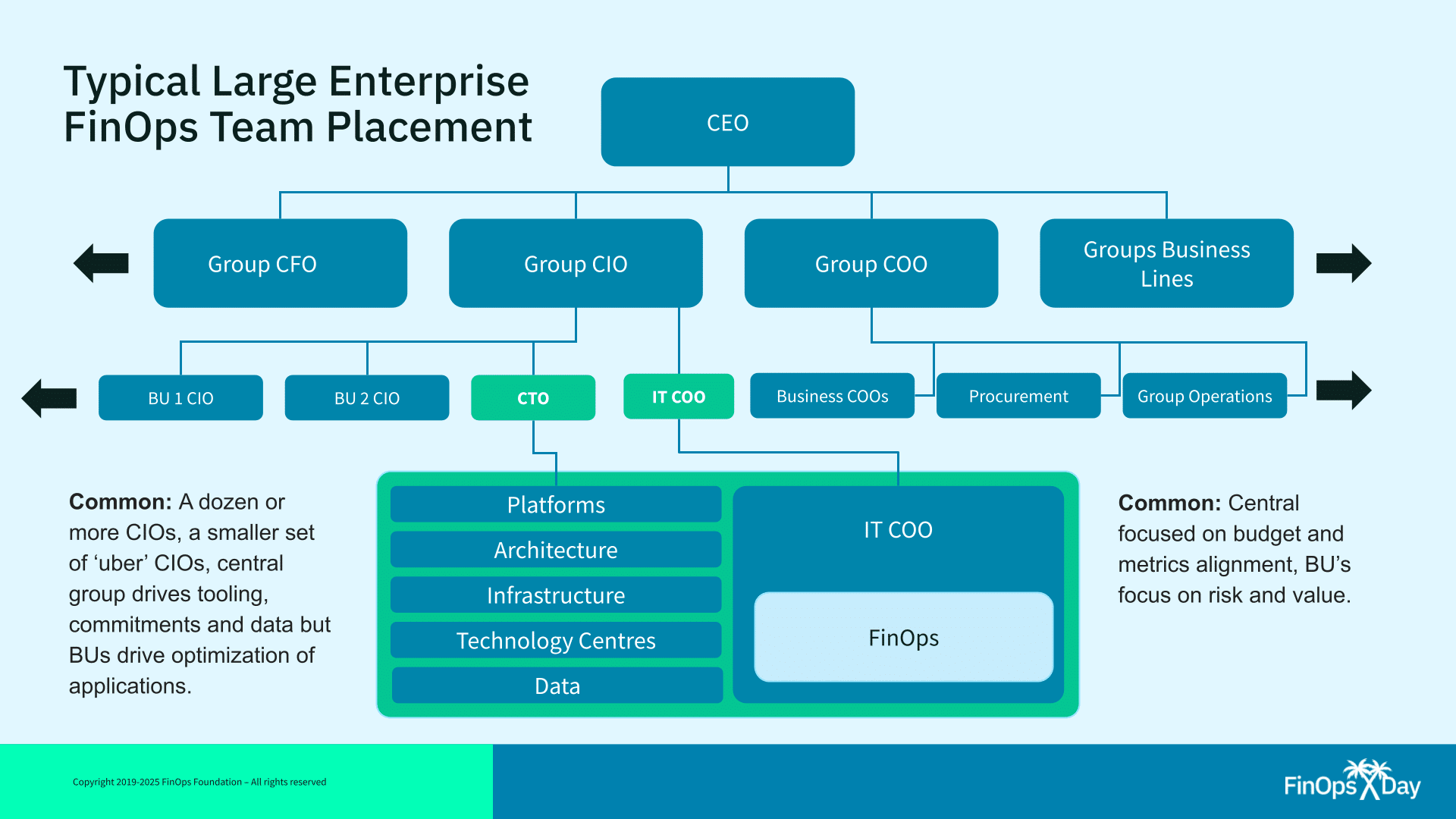

This is an example of FinOps Team placement from an enterprise perspective. Source: FinOps Exec Program

Finding a home for FinOps in the organization structure with proximity to the personas FinOps practitioners most often work with helps to strengthen access, visibility, and influence, promoting collaboration and and keeping silos to a minimum.

Placing FinOps to Drive Business Value

The FinOps function is sometimes perceived as a policing or cost-control function – it is not- but done smartly, FinOps is strategically important as a driver of business value.

Organizational placement should support balanced decision-making between cost, performance, and speed, while also considering broader organizational priorities such as sustainability, risk and security. To achieve this, FinOps must have the authority to influence both technical and financial decisions.

Placing FinOps close to decision-makers is essential. When the function is buried too deep within the organizational hierarchy (particularly in a centralized model) it can limit FinOps’ ability to influence strategic technology and investment decisions. The greater the distance between FinOps and decision makers, the weaker the connection between data-driven insights and strategic action, but too close and the FinOps team collaboration attempts across different functions could be hindered by tight alignment with the executive role.

Nishant Gupta described the alignment of FinOps within Salesforce during the Day 2 keynote of X 2025, explaining that the FinOps function reports into engineering leadership, which also holds responsibility for customer success. This structure aligns development with successful delivery, giving the FinOps team the access needed to collaborate with key personas and influence decision-making – ensuring that technology investments are managed within the same processes that drive innovation and customer success.

Executive Sponsorship Is Key

Strong executive sponsorship also plays a pivotal role in FinOps success. Aligning the function under an executive sponsor, especially during early adoption phases, helps establish credibility, visibility, and momentum. However, the choice of sponsor matters: positioning FinOps beneath an executive who is not educated, motivated, or bought into the FinOps mission will likely yield poor results.

The executive sponsor should be senior enough to influence both finance and technology and to reinforce FinOps priorities across teams. Alignment also affects perception. Placing FinOps too close to finance can reinforce the image of a reactive cost-control function, while aligning too closely with technology can weaken financial rigor and diminish influence over budget decisions.

The optimal placement balances these forces, ensuring FinOps retains both financial accountability and technical credibility. Finally, it is helpful to consider shared goals and metrics when determining organizational placement. When FinOps shares objectives with another function, aligning both under the same executive can improve coordination, accountability, and impact.

Development and Career Paths

Entering Into FinOps

Most FinOps professionals enter the discipline from finance or engineering, reflecting FinOps’ role in bridging the gap between technical and financial practices. However, the paths into FinOps are becoming increasingly diverse. Many practitioners transition from adjacent fields such as product management or procurement, while others grow into the role through rotational programs or internships. Intersecting disciplines like IT asset management (ITAM), IT financial management (ITFM), and security also serve as natural entry points.

Today’s (and tomorrow’s) FinOps practitioners often bring experience in business analysis, automation, data science, engineering, program management, or vendor relations. They share a common foundation of strong analytical, communication, and execution skills and play a key role in driving and evangelizing FinOps practices across their organizations.

Moving Within a FinOps Team

Within FinOps teams, career movement follows both traditional advancement paths and lateral transitions across related roles. Cross-role mobility is most prevalent between the FinOps Analyst, FinOps Data Analyst, and FinOps Engineer/Architect roles as they deepen their technical expertise or deepen their FinOps expertise.

Transitions between the FinOps Financial Analyst and FinOps Analyst roles occur also reflecting the shared analytical and reporting skill sets between these positions. The traditional advancement path of level increases – such as moving from FinOps Analyst to Senior FinOps Analyst – is a pathway for growth within a FinOps team. Ultimately, such growth can lead to a FinOps team member getting promoted to the FinOps Lead position.

Moving On

After spending time in FinOps, some professionals choose to move beyond their current team to explore new opportunities. For some, FinOps may have been along the path of a rotating assignment, others may move on to join another FinOps team in a different organization to bring their experience to a new environment or industry.

It is rather common for FinOps practitioners to choose to transition into FinOps-related roles outside of a formal FinOps team structure—such as FinOps consulting, or working for a FinOps tooling vendor.

FinOps Leads, in particular, may advance into higher-level positions within their organizations, whether through a direct promotion or by stepping into a peer-level role alongside their former leaders. This may be a move to VP of infrastructure, SVP of SaaS & Engineering, Director of cloud services, etc. These career moves reflect the growing value of FinOps expertise across a wide range of business, technology, and operational practices and offer opportunities for further growth into the C-suite.

Conclusion

Every organization’s structure, goals, and culture shape how its FinOps function should be designed and operated. Establishing the team is only the beginning—success depends on filling it with the right people, equipping them with the knowledge, skills, and tools they need, and embedding FinOps into the ongoing practices of the organization.To continue learning, explore the other helpful resources such as:

- Adopting FinOps

- FinOps Training & Certification Resources

- FinOps Jobs

- Internship Quick Start Guide

- FOCUS: The FinOps Open Cost and Usage Specification is quickly becoming the language and format that unifies technology billing data and is a great source for reference as FinOps teams and their responsibilities grow.

Have insights or experiences to share? We’d love to hear from you. Best of luck as you shape and grow your own FinOps practice.

Acknowledgments

We’d like to thank the following FinOps community members for their contributions to this Paper:

Brad Payne

PointClickCare

Carmen May

Southwest Airlines

Mike Rosenberg

Nubank

Rhett Rothberg

U.S. Coast Guard

Anthony “TJ” Johnson

MGM Resorts International

Ekaterina Zemlyakova

Align Technology

Bonnie Firnstahl

Delta AirlinesWe’d also like to thank our supporter(s), Jason DiDomenico for their help.